How do we optimise our vocabulary learning?

Statistical analysis and measurement of efficacy provides a roadmap to optimal vocabulary acquisition

“This is a sea urchin”

Have you ever begun a language course, and in the first lesson you are presented with weird vocabulary you never use?

My personal experience with this came from the “Teach yourself” book series, in which their Hindi course has the word “मारुति” (Maruti - An Indian car brand) in the first lesson. Having learnt the word for an Indian car brand in Hindi, I have proceeded to never use it.

Have you ever noticed how much vocabulary-based learning material purports to teach common vocabulary such as colours, animals or foods? But if you really think about it, how often do you talk about these things?

What words do we actually use when we talk?

We can actually answer the above question fairly accurately, through statistical analysis. By taking a huge collection of varied texts in a language, simplifying all the words to their root forms (lemmatising) and putting them in order of how often they turn up in the text (frequency analysis) you can basically come up with a list of words in your target language, roughly in order of how useful they actually are.

Interestingly, this broadly follows a “pareto distribution” - also known as the 80/20 rule - meaning that most vocabulary you will ever use will appear in the top hundred or so words, with a long tail of less common words. According to the work we do at Pai Technologies, broadly speaking (very broadly) the top 100 words make up about half of all the vocabulary you will hear, the top 1000 about 80%, and the top 5000 about 95%.

Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday…

An interesting point that comes out from this analysis, is that what is commonly thought of as basic vocabulary is completely wrong. This is quite counter-intuitive and generates a lot of pushback for us.

Basic vocabulary is often thought of as colours, days of the week, animals, food, months e.t.c. This is certainly how it’s packaged in many courses in schools and online.

We can’t understand where this idea has come from, but it’s certainly embedded in people’s minds and is found in the structure of many courses and curriculums.

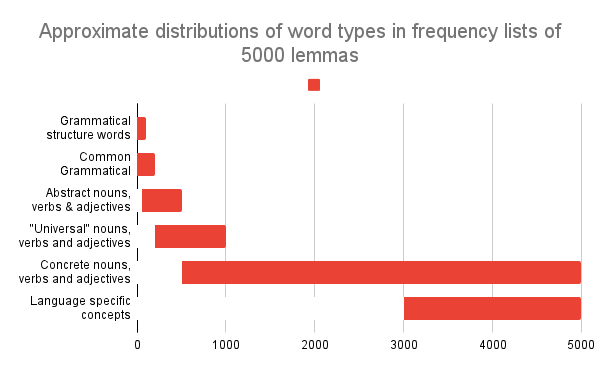

From our analysis at Pai technologies on around 100 languages of varying structures, the most common words in all languages tend to be grammatical function words that help to structure sentences and phrases first of all.

This is followed by common grammatical words such as pronouns, question words, common adverbs, demonstratives, basic conjunctions e.t.c.

Content words such as nouns, verbs adjectives, and adverbs also seem to follow a pattern - the higher frequency words in this category tend to be words that can work with other words to change meaning or qualify phrases (think, seem, believe, know)

Intermixed in this is near universal vocabulary - ‘man’, ‘woman’, ‘child’, ‘house’, ‘road’, ‘money’, ‘tree’, ‘animal’, ‘thing’ and so on..

Only further up the scale do you get more specific nouns and verbs, such as colours, animals and days of the week.

At the top end of the top 5000 words you begin to get vocabulary that’s specific to semantic areas - business, politics, religion etc, as well as concepts that are unique to a culture or a language.

This leads naturally to a great tool for language learners - a frequency list of lemmas. They do exist already in book form for a very limited selection of languages through Routledge, but my company Pai Technologies is currently working on making them available for a far wider selection of languages.

Getting creative

As you learn new words, paying attention to word formation to some extent also helps develop your vocabulary, allowing you to creatively guess at new words. An example of this is from Welsh - knowing that -aeth can be added to words to make abstract nouns. For example:

Gwybod (To know) - Gwybodaeth (Knowledge)

Meddyg (Doctor) - Meddygaeth (Medicine, the field of study)

Cyflog (Wages) - Cyflogaeth (Employment)

Another good method for increasing “stickiness” (that is, how easy you find it to acquire or learn a word) is to look at etymology. Being able to look at words that have a shared root to words in a language you already speak, you can quite quickly form connections and increase your vocabulary.

To us, etymological closeness between languages is a huge part of what makes vocabulary acquisition in different languages easier or harder. It’s far easier for an English speaker to pick up French vocabulary which is broadly recognisable to Englishs speakers- situation, éducation, révolution than it is to learn entirely new words, such as Turkish durum, eğitim, devrim.

This can be expanded further if a learner wants to learn more than one target language - You can look for words between each language that are shared to make the process easier. An example of this would be for learners of hindi

Learning how to learn

Now, we know what to learn - the next step is to focus in on how we learn

As far as we can tell, there’s no singular solution to this - some people thrive on memorisation and use, others follow a more passive approach.

It’s my theory that uptake of vocabulary in a passive situation, such as described by the various acquisition theories, follows a frequency distribution anyway - of course if you need repetitions to acquire a word, then the most common words will be the ones you acquire.

Is it possible to game that though? Surely by “preloading” the high frequency vocabulary in our mind, when we come across vocabulary in a natural setting, it will click quicker, rather than having to go back to look up a word after the fact, or trying to understand it from context?

Here, the phrase “what can be measured can be managed” really comes into its own. By making detailed records of your use of different techniques, you can measure the efficacy of each technique for you personally - be it flashcards, memory palaces, visualisation, passive learning etc. Efficacy here could be measured by the number of words in a session, the amount of time spent on the group, the retention rate going forward in the below equation:

Of course, it’s subjective but after a while you get a feel for what works for you. Only you can learn how you learn.

Ultimately…

I believe that by combining a statistical frequency based approach with a monitored learning pattern, preloading vocabulary into your mind before “naturalisation” or “acquisition” through natural use, this is the most efficient way to learn vocabulary of a language.

I think that acquisition is only half the answer, on it’s own it has a very low efficiency, but that this can be gamed by preloading vocabulary into your mind before interaction with the language.

Thank you for reading!/Diolch am ddarllen!

If you liked this article, please share it or subscribe below! If you are interested in what we are doing, why not check out www.paitechnologies.io or any of our socials!

Thank you. Great article! As a linguist with a passion for morphology, I have particularly found that knowledge of word parts and affixation translates very well to the ESL classroom. I use a lot of lexical games that build vocab fast and which learners tend to enjoy. Also reassuring to have some validation for my instinct towards emphasis on grammar/function words and high frequency nouns over broad topics.

Loved this! I think a common misconception is that language courses keep introducing notions the same way you would teach a baby. Of course, it's fun for babies to recognise colours and animal cries, but completely pointless for adults. My favourite type of courses builds up from simple useful sentences to add more nuances and details, bit by bit 😊